On composing QUIET/LOUD

Part 1: What, broadly speaking, am I doing?

What does it mean for (instrumental) music to be “about” something?

When you listen to this piece, what changes in your perception when you know it’s “about” qubit arrays vs. when you don’t know what it’s “about” at all?

What would change if I told you it’s about… birds? Or plants? Or outer space?

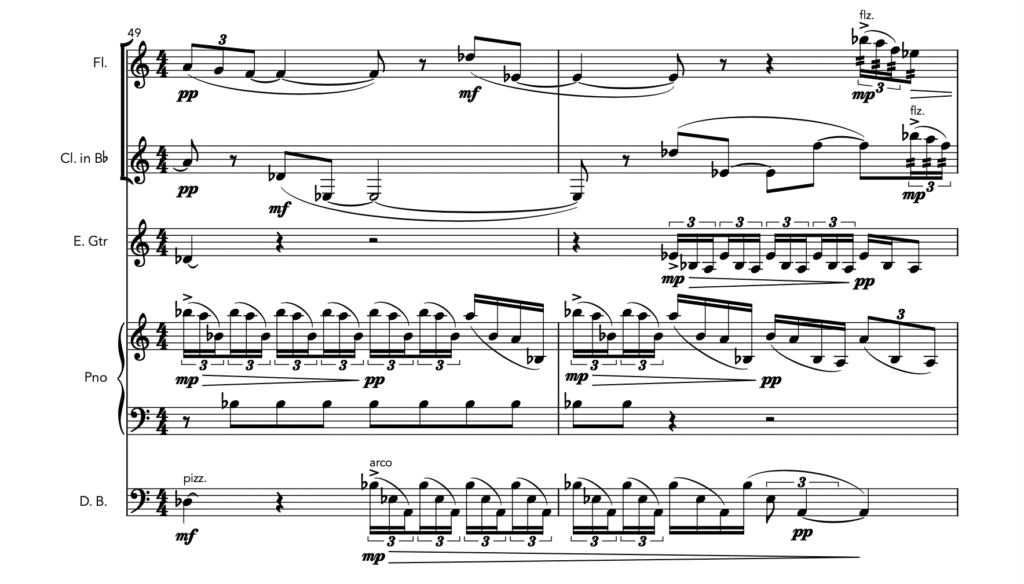

For my first project as the 2025 Fermi Forward Discovery Group Guest Composer, I’m writing a piece about a pair of labs at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, QUIET and LOUD (yes, yes, I chose them because of their names. How could a composer resist?), designed to carry out controlled experiments to better understand the exact effects of cosmic rays on qubit coherence.

So, broadly speaking, what is it that I’m doing…?

I am creating an isomorphism between my understanding of a concept and my organization of sonic material according to a map that exists in my mind.

input (concept) > composer’s mental map > musical output

The order of this process gets mixed around when the music reaches the listener. The listener takes my input and my output, then is invited to draw their own analogy. Perhaps they’ll sense the same connection that I did between concept and sound, or perhaps they’ll make an entirely different connection.

input (concept) + musical output > listener’s mental map

Ok, and what’s the point of this?

I have a two-fold goal when writing music “about” something:

1) To ignite the listener’s curiosity and expand the listener’s understanding of the world.

This is an educational goal, not necessarily a musical one, and it’s part of the reason why the staff at Fermilab have worked very hard to sustain this artist program.

Music can be an invitation. An invitation to contemplate something the listener has perhaps never thought about before, and perhaps otherwise wouldn’t.

I hope that the listener leaves the concert experience with a more specific understanding of quantum computing. I hope that their understanding of this specific part of the world becomes enriched and a little less mysterious.

2) To delight in, and invite the listener to delight in, the richness of human imagination.

However, I will not feel that I’ve done my job if the listener’s only response is, “Ah, now I know what it means for a high-energy particle to reset a qubit to ground state, and I know why that’s a problem for quantum computers.”

I won’t even feel that I’ve done my job if the listener’s response is, “Oh yes, there’s the musical moment where I hear a high-energy particle resetting a qubit to ground state.” Of course, it’s delightful if the listener hears the same analogies between concept and sound that I do. But that’s not really the point.

I have a broader goal…

I revel in the liberating quality of the surreal, the psychedelic, the absurd… and there’s a certain delightful absurdity in writing music “about” quantum mechanics (similar, as the sayings go, to writing about music, dancing about architecture, whistling about chickens, etc.).

It would be possible to take data sets from the labs that I’m writing this music “about” and use an algorithm to transform the data, through a straight-forward mathematical mapping, into sonic representation. But (except for the creativity involved in writing such an algorithm), there’s not a mental mapping going on (at least to the same degree).

It’s the irrationality of perception that’s interesting to me. It’s the thinking about the mental map itself that’s interesting to me. It’s the way I find myself thinking, while I’m writing, “Oh, this will sound like this and create this effect,” but then it doesn’t, and I re-calibrate and try again.

Through this weird process of transforming concepts into sound, I understand my own perception better, and I take great joy in this.

I wish everyone could do what I’m doing. Maybe one day I’ll design some kind of concert experience where everyone in the audience gets to write a little bit of music, or everyone somehow has the opportunity to create something inspired by a concept in the same way that the composer does (input > map > output).

But I know that even when I’m in the listener role, when I’m listening to music that some other composer wrote “about” something, I relish the chance to contemplate the way their perception works.

Recognizing the beauty of human imagination, delighting in inventiveness and discovery… isn’t this the beauty of science, too?

…

How does my map between concept and sound specifically work in this piece? How do I accomplish my two-fold goal?

Next time!

…

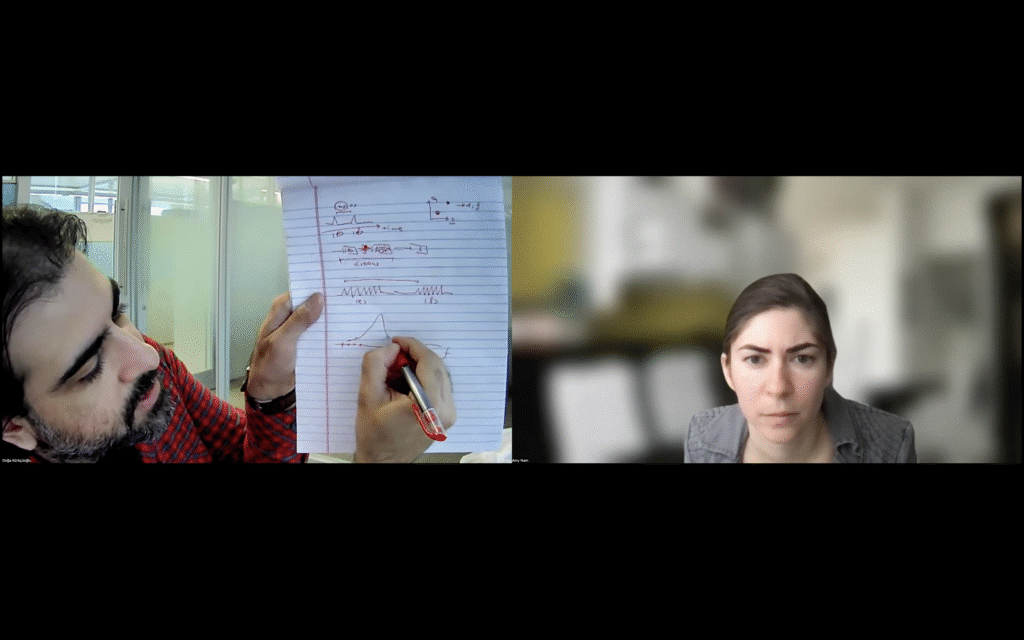

Many thanks to Fermilab scientists Silvia Zorzetti and Doğa Kürkçüoğlu for their time, generosity, expertise, and conversation, to Natalie Johnson, Head of the Office of Education and Public Engagement at Fermilab, and to Georgia Schwender, Visual Arts Coordinator and founder of the Fermilab artist-in-residence program.

QUIET/LOUD will be premiered by the commissioning ensemble fivebyfive in October 2025—more soon!