A teacher once joked to me that your IQ goes up twenty points the moment you slide off the piano bench into the teacher’s chair.

I can since confirm that this is true, and I’ve figured out why. Obviously it’s not a magical property intrinsic to teachers’ chairs… It’s simply that cognition interferes with perception.

When the mind engages in the act of creating, it can become so distracted by its intention, the thing it’s trying to accomplish, that it hardly remains aware of the reality it’s producing. It can’t listen.

Me: “Play the measure, then tell me what you heard.”

Student plays.

Student: “Um, I don’t know. What am I supposed to hear?”

Me: “Did any notes stick out?”

Student: “I don’t think so…”

Me: “Listen again. Your fingernail is buzzing when you play finger 3.”

Student plays again. Bzzt.

Student: “I don’t hear it… Did it happen that time?”

Bzzt. Bzzt.

I pull out my phone. Record student. Play it back.

Student: “Oh, wow!”

Of course, the student’s physical ear, being, as it is, a very cool microphone, registered the same sound waves both times. But somehow, what the brain processed, or became aware of, differed.

As both a teacher and a seeker on the asymptotic journey towards mastery, I am continually in awe at the malleability of perception (both my students’ and my own), or, to borrow Oliveros’s distinction, at the gap between hearing and listening.

The story of Kohn Ashmore presents an extreme example of this gap. After being hit by a car as a child, Ashmore could only speak extremely slowly. Astonishingly, he had no idea that he spoke differently from anyone else until, years later as a teenager, he heard a recording of himself and was devastated.

His story seems hard to believe. However, as a music teacher who regularly observes beginners with no underlying neurological issues abruptly halt at every barline with zero awareness of their doing so, I absolutely believe it. Every bit of our contact with reality is mediated by the mind, and the mind’s representation of the world (including—especially—our own actions in the world) is highly mutable.

At some level, we all seem to be aware of this phenomenon. Less extreme instances are abundant. I offer a few more for your entertainment:

- Holiday board games with the fam:

“We don’t like you, Amy,” everyone is saying. I whine. But a moment later I’m boasting about my superiority. My dad: “If I had recorded what you’d just said and made you watch it back on that TV right there you would understand why no one likes you!”

Oh.

-

When Robert Met Jamie:

Karamo plays the hero a recording of his own words, causing him to finally grasp the extent of his deprecating self-talk.

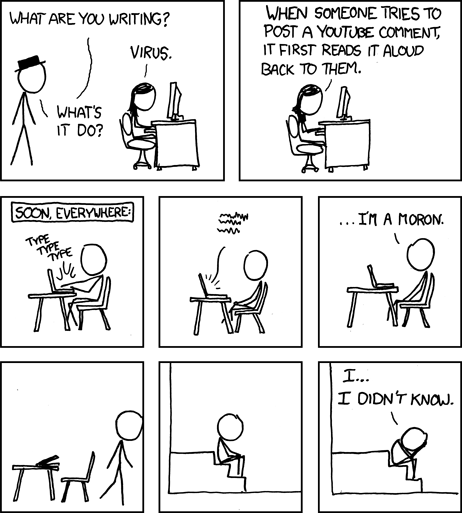

- And of course, this classic xkcd gem:

The roots of this problem run deep: the difficulty of knowing our own selves extends past the sensory into the philosophical. Hannah Arendt writes of “the revelatory quality of speech and action,” observing the disclosure of the agent’s identity implicit in the agent’s every word and deed. However, “more than likely. . .the ‘who’ which appears so clearly and unmistakably to others, remains hidden from the person himself.” Apposite to our topic of listening, Arendt makes note of the particular connection between speech and revelation as “the reason why Plato says that lexis adheres more closely to truth than praxis” (apparently contrary to the common belief that “actions speak louder than words”?).

At any rate, performers (I’ll come back for the composers in a bit), have a straight-forward way to take advantage of the sudden IQ points gained by listening without simultaneously producing the sound: self-recording.

In one sense, given its ease, it’s strange that we don’t more often take advantage of the recording technology each of us carries around in our pocket. Even though I’ve experienced the benefits of recording (most recently last winter while evaluating 20+ full runs of Cosmic Fragments in the lead-up to the DHF WHC), it really wasn’t until one day when I was about to give the same feedback for the fifth time in five minutes that I began using the recording/playback technique during lessons.

Sometimes the recording can be really shocking.

“I can’t believe how bad it is,” one student said.

Commence emergency encouragement administration.

Listening to yourself takes a certain amount of bravery. It can be intensely uncomfortable, even for the best of us.

One might counter that listening to a recording of yourself bypasses the building of the essential skill of listening to yourself in real time while your brain is engaging in the cognition involved in playing. It’s true that the skill of listening while doing must still be mastered. The reasons are abundant:

- 1. You must be immediately able to respond to what you’re hearing when playing with others

- 2. You must be able to respond in the moment to what you are doing during a solo performance.

- 3. Listening back to self-recordings takes twice as long as just listening while playing

- 2. You ought to listen to every sound you produce rather than be limited to just the moments you choose to record

Ideally, the act of listening to recordings of your own playing trains your mind to pay that kind of attention all the time. It’s a shortcut to a picture of what you could/should be continually noticing so that you can return to your real-time playing with a higher standard of awareness. And I find that listening to self-recordings generally functions in this way for me.

How else might you go about training yourself to listen?

The kind of listening I’m describing is similar to the quality of awareness that can be cultivated through meditation and can be described in its terms. The phenomenon of being caught up in cognition is a kind of identification with thought, and listening is resting the mind in that open space of awareness. When listening, you notice sensation—in our context, sound—simply as it appears.

And training your mind to do this, at least according to my understanding, entails continually choosing to direct your awareness back towards itself, again and again, and gradually you hone the skill of observing when you’ve become engrossed in thought and left off noticing (or listening).

It can be done. Like any other skill, listening improves with practice.

…

Ok, great.

Be aware of the sound you’re actually producing instead of the sound you imagine you are producing.

Simple enough concept.

However, there’s a second layer to this. Not only must you cultivate awareness of what’s really happening in the sound you are producing, you must also cultivate awareness of the sound you want to produce.

Wait, doesn’t that completely contradict what I just said?

Isn’t being aware of the sound you want to produce exactly the distracting cognition that must be dropped?

No—it’s not. It’s subtle, but there’s a distinction.

First, an illustration to explain why we need this second layer at all:

When I was an undergrad, I experienced disappointment and frustration while listening to recordings I’d made of myself in preparation for a competition. I could tell my playing wasn’t “good enough,” but I was unable to develop a targeted strategy for improvement other than to just play it a bunch more times to increase my fluency to the point that I could play the piece from my heart.

This was because I was unable to clearly imagine the sound I wanted to produce.

Now, there’s a key difference between letting an imagined sound overwrite your perception such that you aren’t actually hearing what’s happening vs. letting your particular desired sound inspire your moment-to-moment decision-making. When you are doing this second thing, you aren’t imposing another picture over top of reality. Rather, you sense what’s happening and are able to immediately, spontaneously change your playing to bring it into accordance with your desired sound. “It’s like when you taste something you’re cooking and you just know what ingredients it needs more or less of,” my analogy-prone conductor husband said when I picked his brain on the topic.

Recently, I was slightly mortified to listen to my (2017) grad recital performance of the first movement of Wolfram Buchenberg’s Fünf Phantastereien. But it illustrates my point, so I offer it here for side-by-side comparison with my (2024) performance of the same piece in the WHC.

Even though my more recent performance was still far from my ideal, it moves with direction and intention in a way that the first one does not. The contrast, I believe, can’t be fully accounted for by any one factor, such as the increased, more consistent tempo or an improvement in my technique. I attribute the difference to the clarity with which I could perceive my desired sound when approaching the music the second time.

How does one develop this clarity of desired sound?

The mental sound picture can be synthesized from three main activities:

- 1. Imagining the music in the abstract (looking at the score and just imagining how you want it to sound, for instance), singing the lines, etc.

- 2. Experimenting with your playing of the piece to develop ideas (this requires listening and may involve self-recording), also doing things like playing only the structural notes to feel the over-arching flow, etc.

- 3. Listening carefully to recordings or live performances (either of the music at hand or just generally to internalize stylistic practices, etc.).

In the case of the Buchenberg, the second time around, one aid I used for synthesizing the imagined sound picture was a practice click track I created for myself so I could better perceive the changing meters, in addition to using the other methods I’ve described. (No shame in being practical!)

Also, and this can’t be underestimated… it takes time to develop the requisite maturity. Years, decades, even… (I know, I know. Womp womp.)

…

Ok, so, that’s all well and fine for performers.

As a composer, though… well, we composers have a harder time of it.

I think most composers know the experience of revisiting that piece written a few years ago (or that passage written yesterday) and thinking, “How the heck did I think that worked?“

For composers, the cognitive process that interferes with our perception doesn’t stem from the physicality of execution. It comes from something more subtle and thus more hard to relinquish. And so for us, the solution enabling clear perception is not as simple as setting aside the physical component of our process.

When I write music (and here I’ll draw a clear distinction between writing music vs. improvising—I can’t really speak to improvising yet, but my experiences here so far indicate that some entirely different process takes over the brain compared to composing or performing from written/memorized music, and this process seems to involve yet another very distinct way of directing attention)—when I write music, evaluation is bound up with the creation process. As I compose, I mediate between the evolving ideas in my imagination (my intention) and the perceptible sounds coming from my fingers, continually choosing and assessing what to discard, keep, develop. I’m continually reaching into my imagination to hear what needs to come next, even more so than as a performer. And so then when I listen to what I’ve just written (whether that’s through realizing it at the piano, looking at the score and imagining it, or even passively listening to a computer-generated version), it’s difficult to divorce my mind from what it wants to hear, from the thing that I know I am trying to do.

Before this gets messy, let’s take a step back. Just as for instrumentalists, composers also must direct their listening towards a two-fold objective: the music they intend to write, and the music they actually write.

The higher the “resolution” of your imagination, the more direct a process it is to realize your intention on paper. For Mozart, composing was apparently transcription, just from an internal, rather than external, sound source. Most composers, however, don’t hear a fully-realized symphony in their head before putting pen to paper. In fact, for many of us, pulling music from imagination is not unlike hacking one’s way out of an Isengardian slime pit.

So the boundary between intention and realization can be ambiguous. Certainly for me, the music I intend to write co-develops with (and may change in response to) the parts of the piece I’ve fully-realized.

As to how to improve at listening to the sound you intend to write, developing your aural skills obviously plays a large role. That’s fairly straight-forward.

But then there’s the matter of listening to what you’ve actually written. Surprisingly, this part of the process proves to be the more elusive.

When we listen to an earlier work and think, “How the heck did I think that worked?“—what happened? What went on in our past-self brain that resulted in such poor writing?

Betty Edwards attributes the “left brain” with the desire to schematize, simplify, and abstract, and the “right brain” with the ability to perceive things as they are, in all their complexity. “Bad” drawing happens when you draw what you think you see (that is, the simplified, “left brain” version) instead of what you actually see, and it is remedied by shifting into “right brain mode.”

The underlying neurological processes are beside the point for our current purposes: what matters is that this phenomenon aptly describes experience. With composing, I find I am often in “left brain” mode: when I listen back to what I’ve just written, I’m not aware of what I’m actually hearing, so caught up am I in the abstraction of what I’m trying to do. Just as I described in the earlier context pertaining to performers, perception has become distorted by cognition. Instead of being aware of what I’m truly hearing, I’m aware of what I think I’m hearing.

This is why we end up saying, “How the heck did I think that worked?“—you thought it worked at the time you were writing because you conflated your intention with reality, preventing you from properly perceiving what you’d done.

So, how do you go about hearing what your music actually does and not just what you are trying to make it do?

The key, I’ve found, lies in forgetting your intention.

If you want to hear what you’ve written without the distorting context of what you were trying to write, you must forget what you were trying to write.

Ok, so how do you actually do that?

Time can do this. Taking a break from your music and returning. How long? It depends. Maybe overnight. Maybe, if you’ve lived with the music for a long time, it will take weeks or months to forget your intention.

You can also gain some distance from your intention by putting yourself in someone else’s head. A mentor once passed on to me the trick of pretending that you are experiencing a performance of your music from the perspective of the person in the audience right in front of you. What does your music sound like to them? And as a student I certainly found that, even if I gained no other helpful insight, a composition lesson became immediately valuable the moment that I played my music for the teacher and suddenly I experienced it through their mind (or, at least, my imagining of their mind). It can be disorienting. Wow, this transition that I thought I needed is so boring, and why did I leave my first idea so quickly?

These ideas are probably not comprehensive. There may be many other ways to improve at listening to what you’ve actually written. I’ll be sure to write about them when I make those discoveries.

…

What exactly keeps us from listening? Impatience? Reality denial? Just a careless habit?

My deep mistrust of my physical senses prevented me from listening for many years. We’ll leave aside the reasons why that was so, but suffice to say, learning to listen in the way I am attempting to describe here has been a long journey. It began in earnest with mentorship during my undergraduate days and rehearsals for my first studio album. I’ve grappled with articulating these ideas many times before, and I continually return to this space to re-compile the information I continue gaining. Learning to listen proves to be an ongoing process.

I would love to go back to my younger self and reveal this hard-won truth:

Almost all the information for what you you need to do to perform at your desired level is right there, right now, already. This information exists at the nexus of your mind’s imagination, the examples to be gleaned from our living tradition, and your own playing. When you can listen to all three things you will move forward. It will not be instant, but that’s ok. Keep listening!

I can’t go back. So I just tell my students. Probably prematurely. Probably it doesn’t mean anything special to them because you have to really seek it first for it to mean anything.

Oh well.

And of course, my “hard-won truth” isn’t quite true… obviously listening can’t provide all of what you need for skillful physical execution. But listening provides the most important part. The technical challenges that lie along the path to get your body to realize your imagination’s intentions may be mysterious at first. But if you can sonically imagine your goal, and you possess a framework for understanding how your body moves along with a creative problem-solving mindset, you will inevitably figure out technical solutions.

It took me so long to learn that I can love and trust my senses. I am forever grateful to HB for gifting me The Art of Practicing, another instigator in my journey along this path to listening. In fact, that’s a good place to wrap up. Take us home, Madeline Brusser.

“I had been practicing for several hours when I suddenly realized that the sound was coming directly out of the piano. Instead of singing the music in my mind, as I usually did, and focusing on that imaginary sound, I heard the actual sound. I was shocked by its vividness, and by the realization that although this brilliant sensory experience had been available to me for years, I had been missing it. Perhaps you remember a moment when you heard a familiar chord and were unusually struck by its beauty. Or maybe you remember occasions when your movements suddenly became more free and natural than usual. This kind of receptiveness and ease does not have to be a rare event. It is something you can cultivate.”